Synthetic biology aims to create functional devices, systems and organisms with novel and useful functions on the basis of catalogued and standardized biological building blocks. Although they were initially constructed to elucidate the dynamics of simple processes, designed devices now contribute to the understanding of disease mechanisms, provide novel diagnostic tools, enable economic production of therapeutics and allow the design of novel strategies for the treatment of cancer, immune diseases and metabolic disorders, such as diabetes and gout, as well as a range of infectious diseases. In this Review, we cover the impact and potential of synthetic biology for biomedical applications.

By applying engineering principles to biology, synthetic biology has become the science of reassembling catalogued and standardized biological components in a systematic and rational manner to create and engineer functional biological designer devices, systems and organisms with predictable, useful and novel functions. Synthetic biology is able to use an inventory of biomolecular parts compiled over 50 years of molecular biological and functional genomic research 1,2,3,4 , as well as technology that has made it possible to analyse 5,6 , synthesize 7,8,9 , assemble 10 , modify 11 and transfer 12,13 genetic components into living organisms.

Although it has recently become possible to reconstruct a living organism after transfer of a synthetic genome that has been assembled from chemically synthesized nucleic acid pieces 13,14 , the rational design of state-of-the-art biological circuits with predicable functions remains challenging and is apparently limited to a handful genes 15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31 .

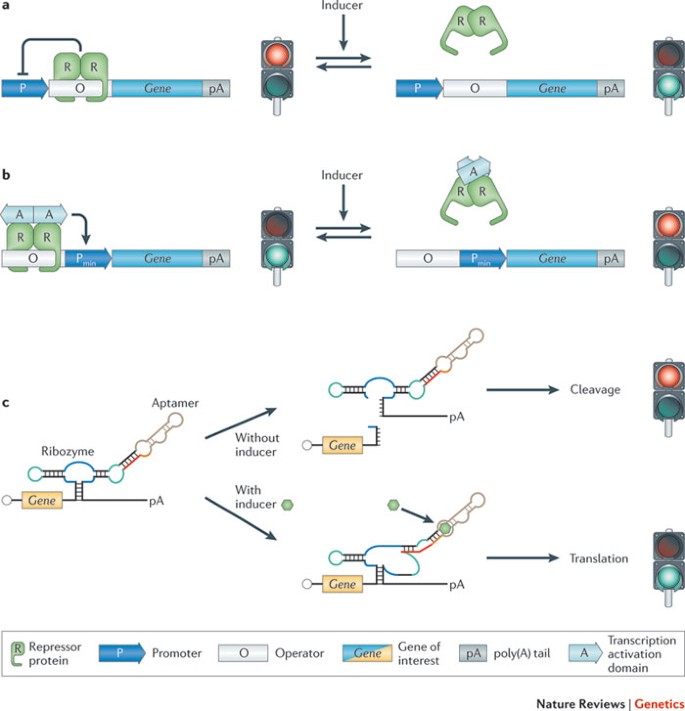

Synthetic circuitry is composed of basic heterologous control components that fine-tune transgene expression in response to specific exogenous cues or endogenous metabolites 32 . These gene switches include trigger-inducible protein–DNA 33,34,35,36 or aptamer–transcript interactions 37,38,39 , which control transcription and translation in response to heterologous and endogenous input signals (Fig. 1). The standardized design of gene switches has improved functional compatibility 40,41 and has enabled the construction of higher-order networks — including multi-trigger inputs and sequential control 42,43 , mutual control 20,23,44,45 and feedback control 16,19,28,46 of circuit components — that are able to provide complex protein expression dynamics with high precision and predictable logic in response to external cues or physiological pathways. Because most control components function in different bacterial and eukaryotic species after minor refinements 36,47,48,49 , gene switches and network blueprints that were pioneered in bacteria or yeast are often fully functional in mammalian cells. Examples of synthetic networks with similar components and circuit topology in bacterial and mammalian cells include: regulatory cascades 42,43 , epigenetic toggle switches 15,20,23,45 , hysteretic circuits 22,50,51 , molecular timing devices 30,52 , synthetic eco-sensing systems, synthetic quorum-sensing systems, synthetic hormone systems 46,53,54 , band-pass filters 21,30,55 and different types of oscillators that program rhythmic transgene expression with a tunable frequency and amplitude 16,26,27,28,29,56,57 . Most of these first-generation synthetic circuits operated in isolation without any interface with the metabolism of the host cell, and they were used to program specific cellular functions using heterologous external input signals 58,59,60,61,62 .

Key challenges that often occur in the biomedical setting are the need for drug–target specificity, precise drug-dosing regimes, minimizing side effects, shortening the diagnosis-to-treatment timelines and avoiding drug-resistance of pathogens. As synthetic biology enables the engineering of complex, high-precision control devices that couple sensing and delivery mechanisms, this emerging science may be able to offer tools that are suited to meeting current biomedical challenges in new ways. A decade after the pioneering synthetic networks were reported 18,20 , the first successful therapeutic applications in animal models of prominent human diseases are starting to emerge 63,64,65 . This Review focuses on the recent progress in synthetic biology towards improving human health, including diagnostic applications, design of novel preventive care strategies, progress in drug discovery, design and delivery, and development of novel treatment strategies, such as prosthetic networks. Synthetic biology holds the promise of providing unique opportunities for major advances in the improvement of human health in the twenty-first century 4,66,67 .

Understanding disease mechanisms

Pathogen mechanisms. The availability of affordable technology for synthesizing and assembling 10 sequences for proteins or for viral 68 and bacterial 69 genomes with increased speed has dramatically improved our understanding of host–pathogen interactions and of disease mechanisms. The synthetic biology principle of 'analysis by synthesis' provides mechanistic insight by combining rapid synthesis, assembly, shuffling and mutation of individual genetic components with straightforward functional analysis. For example, the genome of the H1N1 virus that was responsible for the 1918 Spanish influenza pandemic was synthesized using sequence information from genomic pieces that were extracted from permafrost-conserved tissue samples. Functional analysis of the reconstructed virus provided new insight into the key virulence factors of the pathogen: namely, a haemagglutinin variant that induces membrane fusion without trypsin activation and a modified polymerase that enhances viral replication 68 . The same study also revealed that a combination of eight genes was responsible for the exceptional virulence of the Spanish influenza strain 68,70 . This finding may help to identify the pandemic potential of future virus variants 71,72,73 .

Synthesis and analysis of chimeric viruses have also made a substantial contribution to the understanding of coronavirus zoonoses that were responsible for the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) pandemic of 2002 and 2003. The characterization of the history of the SARS coronavirus, especially its switch in tropism, was particularly challenging, as its direct ancestors could not be propagated in laboratory models. However, after a 30 kb SARS-like bat coronavirus was designed to contain the receptor-binding spike protein of its human homologue, the synthesized chimeric virus was able to replicate in culture and infect mice 74 . These in vivo studies revealed infection-enhancing mutations in the spike protein and established this surface protein as a key factor that is responsible for tropism switches in coronavirus zoonoses 74 . Reconstruction of pathogens by DNA synthesis can also be used for the production of diagnostic high-density antigen arrays 75,76 , such as those used to profile post-Lyme-disease syndrome 76 or the humoural immune responses to hepatitis C and the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) 77 .

Immune systems. Synthetic biology has recently provided new insight into disorders that are related to deficiencies of the immune system, which is known for its particularly complex control circuits and cellular interaction networks. For example, dysfunction of B-lymphocyte activation underlies several physiological disorders 78 . Functional reconstitution and analysis of the human B cell antigen receptor (BCR) signalling cascade in insect cells revealed that BCRs are not activated by antigen-specific crosslinking, as presented in textbooks, but instead have an autoinhibitory oligomeric conformation on resting B lymphocytes that shifts to an active dissociated form when antigens bind 79 . This triggers the signalling cascade, which results in antibody production and the onset of a humoural immune response.

Also, construction of a representation of the complete human peptidome engineered for display on the surface of T7 phages enabled Church and colleagues 80 to discover new autoantigens. They used patient-derived autoantibodies to enrich autoantigenic peptides displayed on the phages; they could then identify the antigens by high-throughput sequence analysis 80 . Knowledge of the antigens that are involved in autoimmune processes is important for understanding disease aetiology, developing accurate diagnostic tests and designing drugs that neutralize autoreactive immune cells 80 .

Disease prevention

Vaccines. High-throughput and high-precision assembly and engineering of entire genomes from well-defined genetic components using synthetic biology principles has provided new opportunities for the design of attenuated pathogens for use as vaccines. For example, primates immunized with virus-like particles that were produced by selective expression of particular chikungunya virus (CHIKV) structural proteins were protected against viraemia after a high-dose challenge; even immunodeficient mice that were treated with monkey-derived antibodies survived subsequent lethal doses of CHIKV 81 . DNA synthesis and assembly has also played an essential part in pioneering a safe live vaccine against the poliovirus 82 . The poliovirus was attenuated by systematic genome-scale changes of adjacent pairs of codons from over- to underrepresented codon sets in viral capsid genes (for example, GCC|GAA is strongly under-represented compared with GCA|GAG, although both encode Ala–Glu). These changes reduced translation and impaired the replication competence and infectivity of the virus. This attenuated poliovirus provides protective immunization in mice and offers a high safety standard given the low probability that all 631 individual changes will revert and thus reconstitute infectious wild-type viruses. The genome-engineering approach used here could represent a general strategy for designing live vaccines against infectious diseases. Other promising vaccination concepts include using antigen-producing immunostimulatory liposomes as genetically programmable synthetic vaccines 83 and the production of heat-stable oral algae-based vaccines to protect against Staphylococcus aureus infections 84,85 .

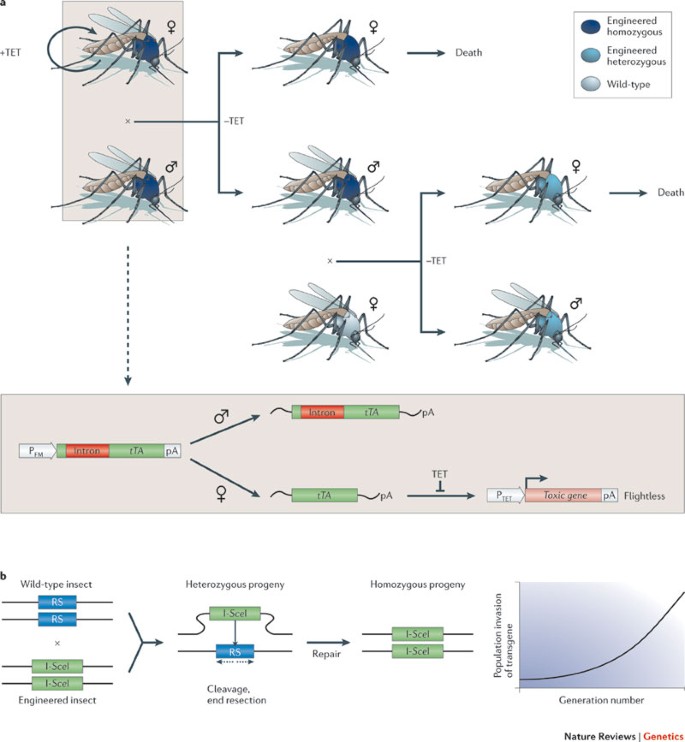

Vector control. Suppression of insect vector populations using transgenic viral strains that harbour conditional dominant-lethal synthetic circuitry may control the transmission of malaria parasites and dengue viruses and could eventually control the spread of untreatable diseases 86,87,88 . Mosquitoes that are transgenic for a tetracycline-dependent transactivator (tTA) that is exclusively expressed in the female's indirect flight muscle can only be propagated in the presence of tetracycline, which represses the transcription of this gene. However, the absence of tetracycline leads to the development of a female-specific flightless phenotype 87,88 . Putting the eggs of this transgenic mosquito into the ecosystem results in male-only releases; female mosquitoes remain grounded and cannot feed, mate or take blood meals, which effectively represents a lethal phenotype. Males do not transmit the disease, but they disseminate the synthetic circuit across the resident wild-type mosquito population 87,88 (Fig. 2a).

Similarly, a synthetic homing endonuclease-based gene drive system could be used to spread genetic modification, such as malaria resistance, from engineered mosquitoes to the field population. Homing endonucleases typically produce a single sequence-specific double-strand break in the host genome that is repaired by homologous recombination using the homing endonuclease gene (HEG) as a template. Consequently, the selfish HEG is copied to the broken chromosome in a gene conversion process referred to as 'homing'. Expressing the HEG I-SceI under the control of a male germline promoter enabled efficient homing in transheterozygous males and rapid genetic drive, which led to HEG invasion in caged mosquito populations 89 (Fig. 2b). By engineering the sequence specificity of other HEGs (for example, I-AniI or I-CreI), the gene drive concept could, in principle, be used to knock in or knock out gene functions that target the mosquito's ability to serve as a disease vector 89 .

Field tests of release of insects carrying dominant lethals (RIDL) technology using first-generation tTA-transgenic mosquitoes have already been conducted in Grand Cayman. First, a small-scale release confirmed that transgenic males could survive, mate with wild females and produce transgenic larvae, and then the full field trial showed an 80% reduction in the numbers of wild mosquitoes about 11 weeks after release. As the study site was not isolated and the surrounding areas contained high densities of wild-type mosquitoes, scoring the actual suppression efficiency remains challenging 90 .

Drug development

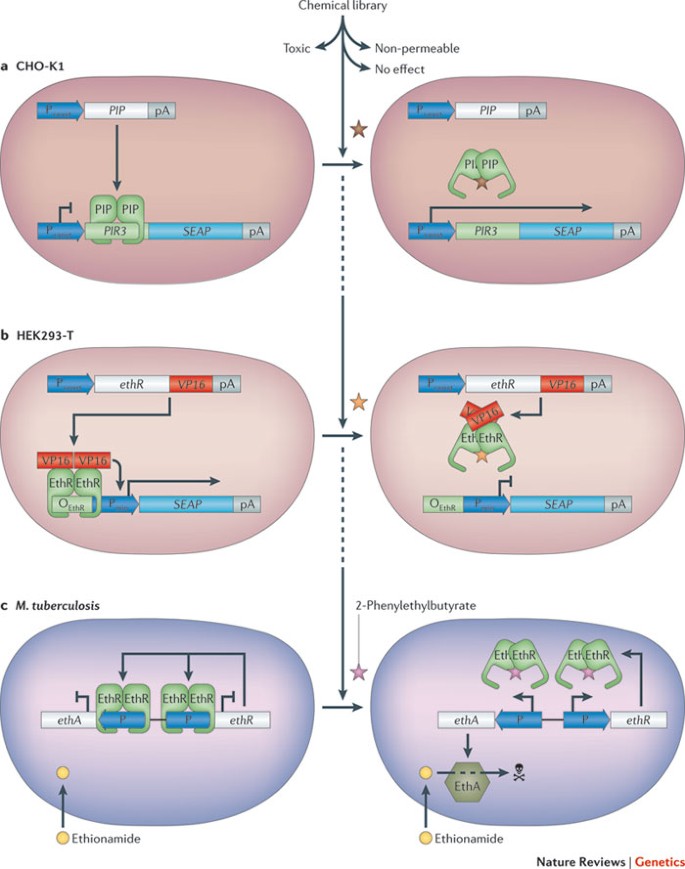

Drug discovery. Synthetic mammalian transcription circuits consisting of a chimeric small-molecule-responsive transcription factor and a cognate synthetic promoter were originally designed for future gene-based therapies, and the aim was to adjust therapeutic transgene expression in mammalian cells in response to a pharmacologically active substance 34,47,49,91 . As most chimeric transcription factors are derived from repressors that manage drug resistance in bacteria (for example, resistance to antibiotics 92 ) and are promiscuous for structurally related compounds, mammalian cells containing such circuitry could also be used in 'reverse mode', as integrated screening devices for the class-specific discovery of new drug candidates 33,93 (for example, new antibiotics 92 ) (Fig. 3a). When mammalian cells that are transgenic for the screening circuit are exposed to a compound library, they detect and modulate reporter gene expression in the presence of a non-toxic, cell-permeable and bioavailable molecule that has a class-specific core structure and corresponding drug activity (for example, antibiotic activity) (Fig. 3b). Using the same screening setup, compounds have been detected that lock the transcription factor onto the DNA, which may block induction of antibiotic resistance in pathogens and render them drug-sensitive 94 (for example, see Bioversys). Using such compounds alongside the specific antibiotic may offer novel anti-infective treatment opportunities and a new life cycle for established antibiotics (Fig. 3c). Other trigger-inducible transcription control systems can be used in this manner as well, such as those that are responsive to streptogramin 47 , tetracycline or macrolide antibiotics 91 , anti-diabetes drugs 95 or immunosuppressive lactones 96,97 .

One example of the efficacy of a transcription circuit system involves the bacterial transcriptional repressor EthR. EthR represses transcription of ethA and so prevents EthA-mediated conversion of the last-line-defence antibiotic ethionamide into a pathogen-killing metabolite 94 . The chemical 2-phenyethylbutyrate, best known for its strawberry flavour, was the first compound found that specifically inactivated EthR and so triggered ethA expression and re-established the sensitivity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to ethionamide (Fig. 3d). Further work revealed other EthR-inactivating ethionamide booster compounds; these have also been successfully tested in a mouse model of human tuberculosis 98 . Restoring drug sensitivity by pharmacological inhibition of master resistance regulators may be widely applicable 94 .

A further example of the use of synthetic circuitry for drug discovery is provided by mammalian cells that are conditionally arrested in the G1 phase of the cell cycle by circuitry controlling the expression of the cycline-dependent kinase inhibitor p27. These cells reproducibly formed a mixture of isogenic subpopulations of proliferation-inhibited cells and proliferating cells that had spontaneously escaped the synthetic cell cycle block 99 . These cells could be used as a cell-based cancer model and could be used to screen for anticancer compounds that selectively eliminate proliferating cells while leaving arrested ones intact 100,101 .

Drug production and drug delivery. The synthetic pathways that are created by assembling enzymatic cascades or networks in bacteria, yeast and plants have been instrumental for the large-scale economic production of high-value drug and drug precursor compounds, as well as for the biosynthesis of new secondary metabolites with novel therapeutic activities. Examples include complex polyketides 102,103 , halogenated alkaloids 104,105,106 and the precursors of the anti-malaria drug artemisinin (which is produced by the company Amyris, for example) 107 and of the anti-cancer compound taxol 108 . For production of these compounds, it was necessary to overcome several challenges, including the functional expression of complex biosynthetic enzymes (such as cytochrome P450 monooxygenases 109 ) and the overall orchestration of the multistep pathway to avoid accumulation of (toxic) intermediate products and to ensure metabolic channelling 60 .

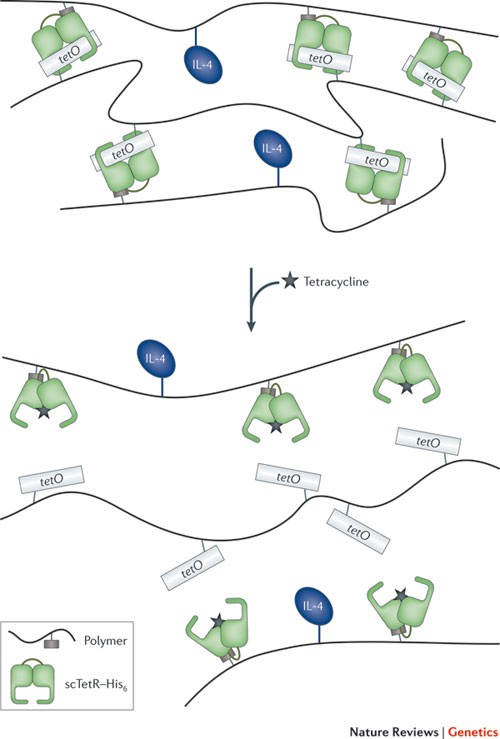

Small-molecule-responsive protein–protein and protein–DNA interactions that are used to pioneer gene switches in mammalian cells 36,49,110 have also been successfully re-engineered in the design of trigger-inducible biohybrid materials for drug delivery 111,112,113,114,115 . Using synthetic protein–polyacrylamide and DNA–polyacrylamide monomers, hydrogels can be produced that dissolve when specific ligands are supplied (Fig. 4). Biopharmaceuticals (for example, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)) supplied during gel formation are loaded into the hydrogel and can be released in a dose-dependent manner after subcutaneous implantation into mice and oral administration of the trigger compound 115 . It is thought that any trigger-inducible protein–protein and protein–DNA interactions could be used to produce drug-sensing and drug-releasing hydrogels 114,116,117 .

Novel treatments for infections

Breaking bacterial resistance by designer phages. Biofilms are surface-associated bacterial communities that are encased in a hydrated extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix that is composed of polysaccharides, proteins, nucleic acids and lipids. They are crucial to the pathogenesis of many clinically important bacteria and exhibit resistance both to the immune system and to antimicrobial treatments, making them difficult to eradicate 118,119 . Collins and colleagues 120 successfully engineered bacteriophage T7 to constitutively express DspB: an enzyme that hydrolyses β-1,6-N-acetyl- D -glucosamine, which is an adhesin that is required for biofilm formation and integrity in Staphylococcus spp. and Escherichia coli clinical isolates. The initial infection of a bacterial biofilm with this bacteriophage (known as T7DspB) results in rapid multiplication of the phage and expression of DspB. Following lysis, T7DspB and DspB are released into the biofilm, which leads to re-infection and degradation of β-1,6-N-acetyl- D -glucosamine. During the process of T7DspB infection, bacterial biofilm cell counts are reduced by 99.997% — over two orders of magnitude greater than when a non-enzymatic phage is used 120 .

In a follow-up study, bacteriophage M13 was engineered to express LexA3, which suppresses the SOS DNA repair system that bacteria require to counteract antibiotic-induced oxidative stress 121,122,123 . Infection by this designer phage sensitizes E. coli to quinolone antibiotics. Use of this phage increases the survival of mice that are infected with E. coli, decreases the survival of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, persister cells and biofilm cells and reduces the number of antibiotic-resistant bacteria that arise from an antibiotic-treated population. It also acts as a strong adjuvant for other bactericidal antibiotics 124 . The designer phage platform can be used to produce other antibiotic adjuvants 124 .

Although it was once abandoned after the introduction of antibiotics, phage therapy is currently being revisited in several clinical trials around the world as the prevalence of multidrug-resistant pathogens is dramatically increasing. Although phage therapy may face clinical challenges associated with development of bacterial phage resistance, phage neutralization by the immune system and pharmacokinetics, the field will certainly receive an impetus from designer phages 125 .

Engineered probiotic bacteria decrease pathogen virulence. Bacteria can communicate with each other using a chemical language known as quorum sensing. Individual bacteria produce and secrete signalling molecules (called autoinducers) that are common to multiple species or are species-specific. These molecules accumulate as the population grows and can bind to receptors that coordinate colony-wide gene expression or manipulate the behaviour of other bacterial populations. For example, Vibrio cholerae produces cholera autoinducer 1 (CAI-1) and autoinducer 2 (AI-2), which trigger repression of key virulence factors. Feeding infant mice with a probiotic E. coli that naturally produces AI-2 and has been engineered to constitutively synthesize CAI-1 significantly increased the animals' survival rate after ingesting V. cholerae 126 . This suggests that such an approach could be an economic strategy to prevent infectious diseases. Unlike antibiotics, quorum-sensing-based interventions do not kill pathogens but reprogram their behaviour; this strategy may be free of selection pressure and therefore may be less prone to develop resistance. In another study, commensal bacteria were equipped with synthetic circuitry to stimulate glucose-dependent insulin production in intestinal epithelial cells 127 .

Cancer therapies

Despite decades of progress in cancer therapy, a major challenge remains: how to specifically target and selectively kill neoplastic cells that develop within native and implanted tissue and relocate within the organism to form metastasis. Therefore, therapeutic strategies that are designed to eliminate cancer cells must be extremely precise to exclusively target diseased tissue while leaving normal tissue intact. Although native cytotoxicity or the constitutive expression of anticancer compounds have demonstrated some potential in animal studies and human clinical trials 128 , trigger-inducible drug expression circuits delivered by tumour-invasive bacteria or tumour-transducing viral particles may improve cancer therapy. Synthetic biologists have recently designed a few anti-cancer devices that provide precise timing, location and dosing of drug production by external cues and could provide greater intra-tumoural effects while minimizing systemic toxicity.

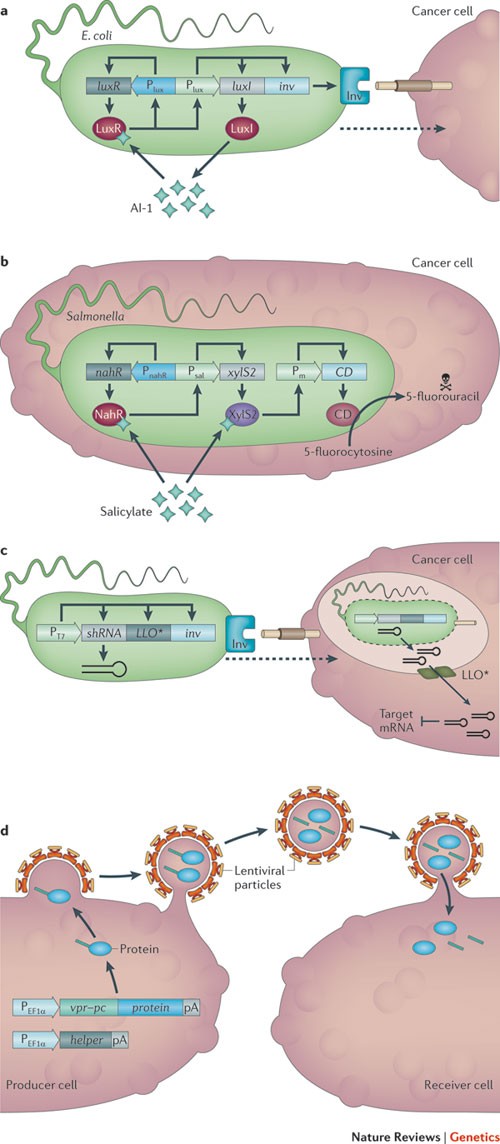

Bacterial synthetic devices. After intravenous injection or oral administration, many bacterial species (for example, E. coli and Salmonella spp.) naturally sense and self-propel towards tumours. These bacteria have also been engineered to selectively invade and proliferate in tumour tissues and to produce cytotoxic compounds as well as reporter proteins for non-invasive follow-up monitoring of tumour regression 128 . These bacteria express flagella to penetrate tissue and chemotactic receptors to promote migration towards aspartate produced by viable cancer cells, ribose released by necrotic tissue or hypoxic regions generated by the hyper-metabolic activities of neoplastic cells. After they have reached the tumour site, the bacteria then either proliferate in the extracellular space or invade the tumour cells. In either situation, selective cytotoxicity was engineered by expressing toxins, cytokines, tumour antigens, pro-apoptotic factors or prodrug-converting enzymes 128 . Non-invasive E. coli has successfully been programmed to invade cultured tumour cells in a hypoxia-responsive or population-density-dependent manner. The corresponding circuitries consist of the anaerobically induced formate dehydrogenase promoter driving the Yersinia pseudotuberculosis invasin gene (inv), which mediates invasion using specific integrin receptors that are typically expressed on tumour cells. Population-density-dependent invasion requires an engineered quorum-sensing circuit that triggers inv expression after the bacterial population has reached a threshold size at the tumour site. This circuitry consists of quorum-sensing receptor LuxR that co-induces luxI (which encodes the enzyme producing the quorum-sensing messenger autoinducer 1 (AI-1)), and inv. AI-1-triggered, LuxR-mediated expression of luxI represents a positive feedback loop that amplifies inv expression and AI-1 production; this coordinates and broadcasts the invasion order across the entire population 129 (Fig. 5a).

Tumour-invading bacteria have also been engineered for trigger-inducible drug expression after entering tumour cells. In addition to L -arabinose- 130 and γ-irradiation-induced 131 drug expression, a synthetic salicylate-triggered expression device has been used to control expression of drug components following systemic administration of the trigger molecule in mice in tumour cells that have been invaded by Salmonella spp. 132 . The device is based on a circuit that is derived from Pseudomonas putida, which controls expression of cytosine deaminase in a salicylate-inducible manner 132 . Mammalian cells normally lack cytosine deaminase, which means that they are resistant to 5-fluorocytosine because this enzyme is needed to convert 5-fluorocytosine into the cytotoxic molecule 5-fluorouracil. Tumour-bearing mice were injected with attenuated Salmonella enterica engineered with the P. putida-derived circuit and then treated with 5-fluorocytosine. The mice showed significant tumour regression when fed with acetylsalicylic acid (Aspirin) 132 , which is rapidly converted to salicylate after intake by the animal (Fig. 5b).

RNAi is a potent and highly conserved mechanism for the targeted knockdown of mRNA translation by small RNAs. Non-pathogenic E. coli was engineered to express a short RNA hairpin that triggers RNAi against catenin β-1, which is a colon-cancer-specific oncogene 133 . These bacteria, which were also engineered to express proteins to mediate cellular invasion and escape from the phagosome, were administered orally or intravenously and significantly reduced catenin β-1 levels in the intestinal epithelium and in human colon cancer xenografts in mice 133 (Fig. 5c). Combining various bacterial anti-cancer treatment strategies may increase safety, specificity and efficiency in future clinical trials.

Viral synthetic devices. Viruses have also been successfully engineered to transduce specific cells by expressing epitopes that are recognized by particular cell-surface receptors and to express prodrug convertases and cytokines for use in cancer therapy 134 . Most of these oncolytic viruses carry coding viral nucleic acids, which may cause side effects owing to recombination with the host chromosome or proviral elements that are already in the host cell. Recently, synthetic viral particles have been designed that lack coding nucleic acids and that exclusively package therapeutic proteins, which can be released in a dose-dependent manner 135 . For example, viral particles carrying linamarase from Manihot esculenta were injected into human breast cancer xenografts in mice that had been treated with the non-toxic natural product linamarin; these viruses triggered efficient tumour regression owing to the cyanide produced by linamarase-mediated conversion of linamarin 135 (Fig. 5d). Similarly, protein-carrying viral nanoparticles have been used to deliver site-specific DNA recombinases, such as FLP, to precisely integrate or excise genetic components on the host chromosome 136 . They might also be used to deliver native or chimeric transcription factors that could transiently control the expression of target genes that are involved in therapeutic interventions, lineage control or induction of pluripotency 137 .

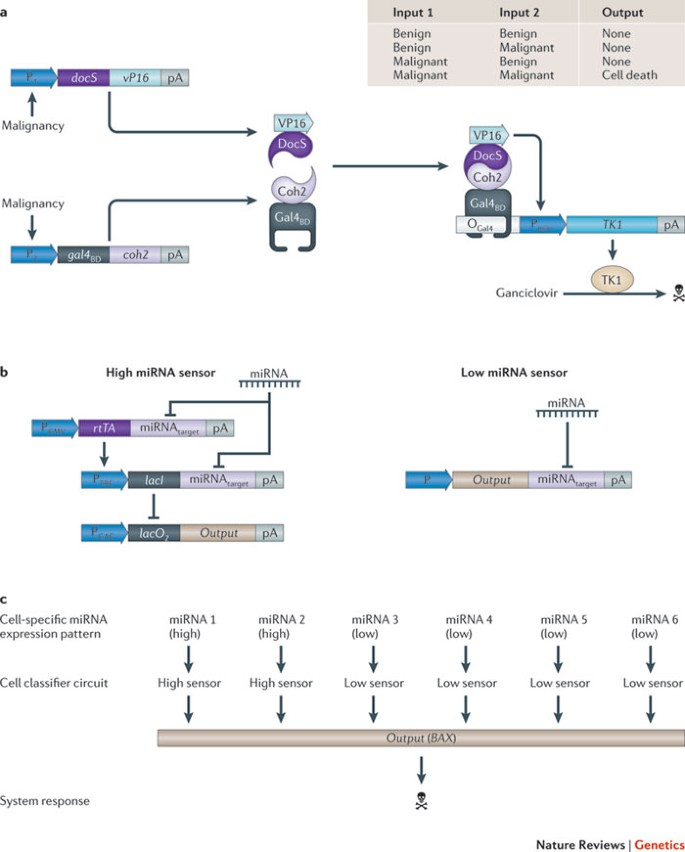

A transformation sensor for cancer therapy. Gene therapy advances for cancer include virus-mediated delivery of cytotoxic effector genes controlled by cancer-specific promoters 138,139 or delivery of chimeric adaptor proteins to link tyrosine kinase signalling to the apoptosis-inducing caspase machinery 140 . Most promoters and control circuits that coordinate simple reactions such as these are inherently noisy and only allow linear responses, which means limited control of specificity and efficacy. However, using two internal input signals can improve fidelity, mediate sharp response profiles and ensure robust biochemical processes 141 . Using decision-making circuits as blueprints, Nissim and Bar-Ziv 142 designed a tunable dual promoter integrator (DPI) to target cancer cells precisely. The DPI consists of two native promoters that are concurrently activated by two independent transcription factors. Each cancer-sensing promoter produces a different fusion protein in proportion to its activity, and these two proteins assemble together as a chimeric transcription factor. This transcription factor then activates a synthetic promoter that controls expression of the herpes simplex virus type 1 thymidine kinase (TK1), which is cytotoxic in the presence of nucleotide analogues, such as ganciclovir (Fig. 6a). The DPI could be optimized for a specific cancer cell type by using different combinations of input promoters and effector genes, as well as by modulating the assembly efficiency and half life of the chimeric transactivator components. So far, a set of three promoters have been characterized in detail, but the DPI design may accommodate other suitable promoters.

The recently developed 'cell-type classifier' is conceptually similar to the DPI, as it can also be programmed to destroy cells that express a specific set of neoplastic markers 31 . The cell-type classifier combines transcription and translation control components in a single scalable synthetic circuit that senses expression levels of a set of (currently up to six) endogenous microRNAs (miRNAs); it triggers an apoptosis-inducing response only if those levels match a preset profile. The cell-type classifier combines sensor modules for the detection of highly and lowly expressed miRNAs (Fig. 6b). For clinical implementation, both the DPI and the cell-type classifier must either be delivered to the cancer tissue, or they must provide a fail-safe mechanism that constantly eliminates transforming cells from engineered tissue implants.

Other emerging tools for biomedicine

Novel treatment strategies will require new technologies to sense and control disease. Synthetic biologists have designed new devices that could sense key physiological activities and have found new ways to dose therapeutic interventions precisely in response to external physical cues. Such synthetic devices could have wide-ranging biomedical applications.

RNA controllers of cell proliferation. Thus far, synthetic control devices that are designed to interface with host metabolism and to reprogram cellular behaviour have largely been limited to heterologous transcription factors. RNA controllers may represent an alternative. They are straightforward to design and can be integrated into a single expression unit containing sensors (aptamers), gene-regulatory components (ribozymes) and effector transgenes 39,143,144 . The inherent modularity and compatibility of RNA-based control components enables them to be independently optimized or exchanged. For example, an RNA control device consisting of a drug-responsive aptamer linked to a ribozyme in the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) of a cytokine expression unit enabled trigger-inducible inactivation of ribozyme-mediated transcript cleavage and full transgene expression in the presence of the input signal 145 . This synthetic RNA control device was applied to control proliferation of engineered primary human T cells and enabled external control of the expansion of transgenic T cells that are implanted into mice. Synthetic RNA control devices could provide the advance that is necessary to enable T cell therapy 145 ; by contrast, state-of-the-art, trigger-inducible expansion of engineered T cells using chimeric antigen receptors has only led to moderate proliferation and poor survival of T cells in clinical trials 146,147 .

Another use for synthetic RNA is the design of programmable sensor–actuator devices that convert levels of an intracellular protein into a discrete high or low transgene-expression state 148 . The RNA devices consist of a three-exon, two-intron minigene followed by the transgene. The introns contain protein-sensing aptamers, and the central exon includes a stop codon. Binding of the protein to the aptamers controls splicing of the minigene; when the central exon is spliced out, the transgene is expressed at high levels, and when it remains unspliced, the transgene is expressed at low levels. Such a device was configured to sense subunits of nuclear factor kappa B (NFκB) or β-catenin (which are neoplastic markers) and to express the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase. Thymidine kinase renders cells susceptible to ganciclovir, so this device only operated as a cancer kill switch in the presence of the cancer markers and gangcicolvir 148 . The modular configuration of the RNA sensor–actuator device allows it to be tailored to different intracellular proteins and even to multi-protein input using specific intronic aptamers. Also, responsiveness and performance can be tuned by placing the aptamers at different locations within the introns. The availability of compact RNA sensor–actuators that are easy to design and to alter and that control transgene expression in response to intracellular levels of key proteins may also improve the ability to link metabolic disease states with gene-based therapeutic interventions.

Optogenetic devices in blood glucose homeostasis. Light is becoming increasingly popular as a traceless, molecule-free input signal for triggering transgene expression in living systems. Bacteria have been engineered to record projected images with gigapixel resolution 149,150,151 and to adjust transgene expression in response to multi-chromatic input 150 , and now genetic light switches have also been designed to control gene expression 152 and shape of mammalian cells 153 .

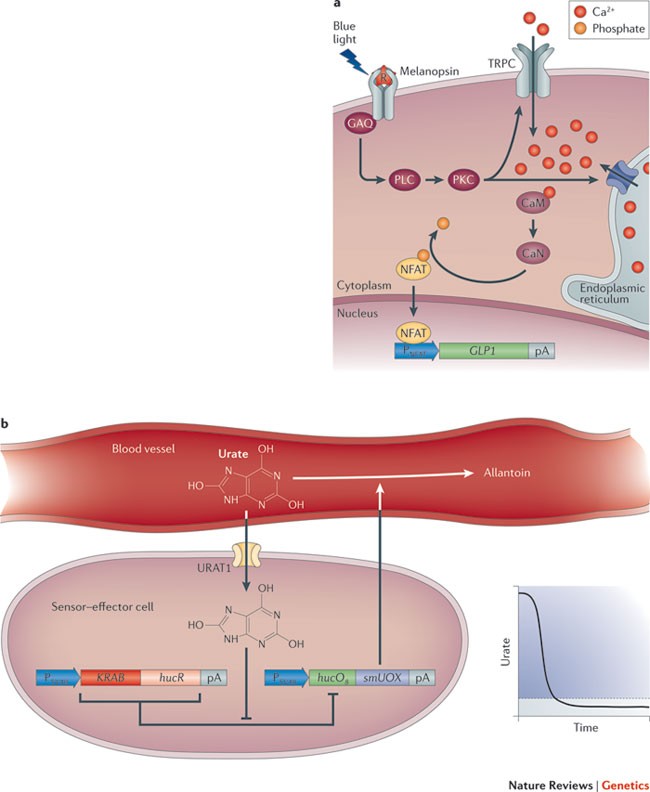

Devices that convert light pulses into transcription may foster novel therapeutic opportunities in future gene- and cell-based therapies and may improve the manufacturing of difficult-to-produce protein pharmaceuticals, such as cancer therapeutics. An illustrative example is light-controlled expression of the glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP1), which is a promising drug candidate for the treatment of type 2 diabetes 65 (Fig. 7a). An optogenetic device that enables light-triggered gene expression in human cells was designed. This involves ectopic expression of melanopsin in human embryonic kidney cells and functional rewiring of signalling downstream of melanopsin; the cascade integrates blue-light-pulse-triggered photoreception and produces a reversible and sustained intensity-dependent transcription response. When placed in hollow fibre containers and implanted into mice, transgene expression in the engineered light-sensitive cells could be controlled remotely by an optical fibre 65 . Illuminating mice that carried subcutaneous implants of microencapsulated photo-responsive cells also enabled transdermal control of transgene expression and of corresponding protein levels in the blood of treated animals. This system was able to attenuate glycaemic excursions and to control glucose homeostasis in a mouse model of human type 2 diabetes 65 .

Prosthetic networks. Prosthetic networks are synthetic sensor–effector devices that act as molecular prostheses. When engineered into cells and functionally connected to host metabolism, they sense, monitor and score disease-relevant metabolites, process off-level concentrations and coordinate adjusted diagnostic, preventive or therapeutic responses in a seamless, automatic and self-sufficient manner.

An example of the use of a prosthetic network is the sensing of metabolites to improve control of urate homeostasis (Fig. 7b). Moderate levels of uric acid, which scavenges radicals, are deemed to be beneficial. However, a transient surge in uric acid that is released by dying cells during cancer therapy leads to tumour lysis syndrome, and chronic hyperuricaemia can result in gout. Humans are particularly sensitive to imbalances of urate homeostasis because they lack uricolytic activity. A prosthetic network that constantly monitors blood urate concentrations and restores urate homeostasis by controlled expression of a urate oxidase — which reduces excessive urate concentration while preserving levels that are suitable for radical scavenging — could represent a treatment strategy for hyperuricaemic disorders 64 . In brief, human cells that contain such a prosthetic network have recently been designed by combining: the uric acid sensor HucR 154 , which manages oxidative stress protection in Deinococcus radiodurans; the human uric acid transporter URAT1 (also known as SLC22A12), which increases the intracellular uric acid levels and thus the sensitivity of the prosthetic circuit; and a secretion-engineered urate oxidase (smUOX) that is clinically licensed for the treatment of the tumour lysis syndrome 155 . The prosthetic uric-acid-responsive expression network (UREX) was able to sense uric acid concentrations precisely and to activate secretion of smUOX when the uric acid concentration was at pathologic levels. Secretion of smUOX is stopped as soon as the uric acid concentration has returned to the homeostasis level. This was impressively demonstrated when UREX-transgenic cells were implanted into urate-oxidase-deficient mice, which develop acute hyperuricaemia with symptoms that are similar to human gout. UREX was able to degrade urate and restore urate homeostasis in the blood, resulting in the dissolution of uric acid crystal deposits in the kidney of treated animals 64 . Its straightforward design may allow UREX to serve as a blueprint for the assembly of other prosthetic networks that sense metabolic disturbances and circulating pathologic metabolites.

An artificial insemination device. Artificial insemination is standard practice to facilitate both human reproduction and livestock breeding. Because of broad variations in oestrus expression and ovulation timing, coordinating sperm delivery with female oestrus is still a major challenge. Ovulation is triggered at a specific time when the pituitary gland releases luteinizing hormone, which binds to the luteinizing hormone receptor (LHR) and coordinates the release of the oocyte. By integrating synthetic signalling cascades with advanced biomaterials, Kemmer and colleagues 63 designed an artificial insemination device that coordinates sperm delivery with oestrus control. The artificial insemination device consists of cellulose sulphate capsules containing bull sperm and sensor cells 63,156,157 . The sensor cells are engineered to express LHR constitutively so that when it is activated, it triggers expression of cellulase that can be secreted. After implantation into the cow's uterus, the sensor cell line constantly monitors the animal's luteinizing hormone levels, and the oestrus-triggered surge in luteinizing hormone levels leads to the production of secreted cellulase, which degrades the implanted capsule and results in the timely delivery of the sperm and successful conception. Fine tuning of the designer cascade could enable its use in other species, including in humans.

Perspectives and conclusions

In recent years, synthetic biology has substantially advanced strategies for classical biomedical applications, such as pathogen characterization 68,70,74 , disease analysis 78,79,80 , diagnostics 75,76,77 , screening assays 33,92,94,100,101 , drug production 105,106,107,108,158 and vaccination 81,82,85 . This progress may imminently develop into shorter drug discovery 94,98 and drug development timelines, increased precision of drug delivery 112,114 and production of new and more affordable medicines 104,105,106,107,108,109 . Ultimately, sophisticated therapeutic sensor–effector devices that can sense disturbances, seek out pathological conditions and restore function are on the roadmap. Such therapeutic networks that connect diagnostic input with therapeutic output may provide all-in-one diagnostic, preventive and therapeutic solutions in future gene- and cell-based therapies. Matching diagnostic outcome with high-end therapies has recently become a focus of the pharmaceutical industry, which has declared personalized medicine as the treatment strategy of the future. Tools that will have a tremendous impact in future biomedical applications include: using light-activated triggers to bring about a precise therapeutic response in cells 65 , programming bacteria to seek and destroy cancer cells 128,132,133 and using synthetic circuitry to keep crucial metabolites at homeostatic levels 64,65 , to manage disease-controlled expansion 145 or to eliminate specific cell populations 31,148,159 . Recent work has shown that this is, in principle, possible and that some devices are working as expected and are producing a therapeutic impact in animal models of human diseases 64,65 . Implants consisting of engineered microencapsulated cells represent a way of introducing prosthetic networks with a predefined function instead of directly targeting the host cells with the genetic material. Although implants containing cells with engineered prosthetic networks are certainly the most promising way forward, they will limit biomedical applications to extracellular disease metabolites that can be therapeutically addressed through the vascular system.

However, there is still a long way to go until synthetic-biology-based biomedical devices will be a clinical reality. Placing therapeutic circuits in specific cells of a patient and making sure that there will be no interference with human metabolism are the most important challenges. Therefore, clinical use of synthetic-biology-based devices and therapeutic scenarios will face the same scientific, ethical and legal issues as any gene- and cell-based therapy, but they may offer more complex control dynamics and are therefore expected to have a higher therapeutic impact. Although none of the synthetic devices, prosthetic networks and related products that are pioneered by synthetic biologists have yet been used in the clinics or in clinical trials, the stage is set — with novel treatment strategies available and the commitment of the pharmaceutical industry in place — for synthetic biology to deliver the biomedicines of the twenty-first century.

Work in the laboratory of W.W. is supported by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Community's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) ERC Grant agreement number 259043-CompBioMat and the Excellence Initiative of the German Federal and State Governments (EXC 294). Work in the laboratory of M.F. is supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant number 3100A0-112549) and in part by the European Community Framework 7 (Persist).