In the ever-evolving landscape of present-day employment contracts, employers and employees are often faced with the dilemma of interpretation and enforcement of non-compete clauses. These clauses which were earlier reserved for senior-level and key managerial personnel have now penetrated almost every employment contract, impacting employers, employees and professionals at varied levels.

Simply put, a non-compete clause restricts an employee’s ability to work for a competitor or engage in similar businesses, typically within a defined geographical area and for a specified period, which may be during and also post their exit from the current job. These clauses inter alia aim to protect an employer’s trade secrets, proprietary and confidential information, and customer relationships from potential exploitation by former employees.

The rapid pace of technological advancements, the rising gig economy and increasing remote working options have transformed the traditional notions of employment, due to which enforcement of non-compete clauses has become more complex and is often caught between safeguarding employer interests and protecting employee rights. In this article, we have delved into the intricacies of such clauses.

Historical Perspective and the Rule of Reasonableness

Indian courts have historically adopted a strict approach to non-compete clauses, citing Section 27 of the Indian Contract Act, 1872 (“ICA”), which prohibits agreements that restrain trade, save when the restriction is tied to the sale of goodwill. This strict stance stemmed from the belief that such clauses could unduly restrict an individual’s right to work and earn a livelihood.

However, as India’s economy matured and businesses grew more complex, courts began to recognize the need for a more nuanced approach. The landmark case of Niranjan Shanker Golikari v The Century Spinning Company marked a significant shift, introducing the concept of the ‘rule of reasonableness.’ This rule considers factors such as:

The ultimate objective is to ensure that the non-compete clause safeguards the employer’s legitimate interests, while simultaneously not unduly restricting the employee’s ability to work. Of course, the determination of what constitutes legitimate interest is contingent upon the facts of the matter and lies within the discretion of the presiding court. Resultantly, a plethora of judgments ensued after the Century Spinning Case — some relying on and upholding the concept of reasonableness; yet some, declaring Section 27 of the ICA to be steadfast in its intent, rendering any attempts to deviate from it as void.

That said, the burden of proof lies heavily upon the claimant, and once discharged the onus of proving otherwise nevertheless shifts to the counterparty [3]. The burden of proof would be the reasonableness of the restriction as well as the necessity of the restriction to protect the interest of the employer/party seeking to enforce the covenant.

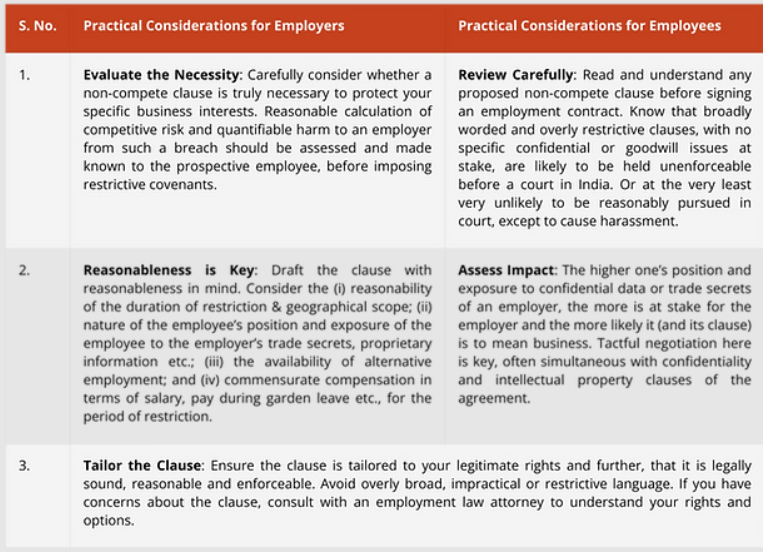

Practical Considerations

Conclusion: A Balancing Act

We believe that it is imperative to strike a balance between protecting an employer’s legitimate business interest and the employee’s right to pursue gainful employment, after careful consideration of ethical, legal and practical factors. The key here is the reasonableness of such clauses. It is our personal view that reasonable, practical, nuanced, enforceable and tailored clauses are a prerequisite in holding the reasonableness of such terms.